Campus Technology 2015

/A summary of my presentation at the 2015 Campus Technology conference in Boston. Read more …

Read MoreLearning How to Learn: Growing a PLN

/ As a teacher, professor, or instructor at any level, one of the keys to survival is knowing how to continually learn and grow. Personal learning is one of the characteristics of teaching effectiveness. It is easy to get stuck in a rut in any profession, but teaching is especially vulnerable to this tendency because teachers are continually having to adapt to new students, new materials, new mandates, and new approaches to learning. It's surprisingly easy to just find a comfortable middle ground and float along, usually at the students' expense.

As a teacher, professor, or instructor at any level, one of the keys to survival is knowing how to continually learn and grow. Personal learning is one of the characteristics of teaching effectiveness. It is easy to get stuck in a rut in any profession, but teaching is especially vulnerable to this tendency because teachers are continually having to adapt to new students, new materials, new mandates, and new approaches to learning. It's surprisingly easy to just find a comfortable middle ground and float along, usually at the students' expense.

One of the most rewarding endeavors I have ever pursued as an instructor is connecting with other educators in my PLN (personal learning network). Learning from other instructors, most of whom I will never meet in person, has expanded my knowledge, skills, and understanding of the teaching and learning process in amazing ways.

What do you mean by "connect"?

Over the past several years, I have participated in communities of practice with other educators around the world. Some of them live in my city, others live on the other side of the planet. I have used a variety of digital tools to create my PLN, all of which have contributed to my professional growth in some way.

Blogs

Over time I have created a list of blogs by like-minded educators who have a similar goal: design and implement innovative teaching strategies to increase student learning, engagement, and motivation. I use tools such as Feedly and Flipboard to aggregate blogs so I only have to look in one place to see updates and new content. Most of these blogs are focused on educational technology and classroom teaching, but just because I use technology to stay up to date does not mean I am only learning about technology. I have learned strategies for facilitating discussion, embracing diversity, addressing cheating, and many other teaching topics.

Communities

In addition to following a collection of blogs, I also participate in different communities. These communities are hosted on social networking sites, and they are pretty easy to follow. For example, I am currently in about 15 Google+ communities, and I can get updates on new posts by scrolling through my news feed. I also follow about 30 different educators and innovators through Twitter, and it is pretty easy to scroll through updates to see their latest ideas and discoveries. Finally, I have joined a few different LinkedIn groups, and I get a weekly digest of anything that has been happening there. The point is, I do not have to spend a lot of effort staying updated on what is going on in these different communities, and when I do get updates I almost always learn something new.

Participation

The final way that I have gotten involved in my PLN is to actually participate and be a contributor. This blog has become my channel for processing, sharing, and reflecting on my own teaching ideas. Most of my posts would just sit isolated in cyberspace if I did not share them with my communities. By not only learning from others in my PLN, but also sharing my own experiences, I have become an active participant in this global experiment known as the World Wide Web. It's one thing to try other people's ideas, but it is downright exciting to find out other people are learning from me and trying MY ideas with their students.

Casting the Vision

This semester in my graduate-level technology class, I decided to do something new. I created a semester-long project where my students would build, engage, and participate in their own PLN. The first phase required them to join various communities of interest and follow different folks on blogs and Twitter. I gave them some suggestions, but I know some of the students have already branched off into their own interests. The second phase was for them to share what they were learning within a private Google+ community that we all joined. This way we could share what we were learning in a safe, secure place. The last phase, which is still underway, will be for the students to share what they are learning within the communities they have joined. This may mean sharing items they find, writing and sharing their own blog posts, or participating in discussions online. Since this project is currently underway, I can't really measure whether or not it is going well. It's going better than I anticipated, but I will not know the extent of everyone's participation until a few more weeks have passed. It took me a few years to become fully immersed in my PLN, so I can't expect a full conversion from my students before we've even reached midterm. But I'm committed to see this through. I cannot understate the value of my experience learning from and engaging with other innovative teachers. It has been transformative and deeply rewarding, even though some of those other educators have no idea I am learning from them. I would be remiss not to provide the same opportunity to my students.

So, what strategies or projects do you use to get teachers immersed in their own PLN?

Schoolification

/ I have been thinking about gamification a lot lately. I teach a really big class full of energetic undergraduates, and I want to make the class better. It is already pretty darn good, but there is always room for improvement. One way to do this is to add game elements to some of the more mundane aspects of the course.

I have been thinking about gamification a lot lately. I teach a really big class full of energetic undergraduates, and I want to make the class better. It is already pretty darn good, but there is always room for improvement. One way to do this is to add game elements to some of the more mundane aspects of the course.

As an aspiring Teaching and Learning scholar, I dug into the literature on gamification and game-based learning (and trust me, there is A LOT of it!) to investigate possible frameworks and suggestions for a successful implementation of game-based learning. One framework that has been really helpful for me as I plan some game-based elements into my course was proposed by Bunchball, a corporate gamification company. As stated in one of their white papers, there are 6 elements that serve as the building blocks to all successful games. Coincidentally, these game elements interact with game dynamics that are associated with basic human desires that tend to motivate and engage people within a gaming experience.

[table id=1 /]

When I look at this table, I see many similarities and natural applications to education. The way the education system is currently structured, there is already a pretty heavy dose of competition, achievement, reward, and status. There is also some possibility for self-expression and altruism, depending on the way a course is set up. So, I understand that education and gamification go hand-in-hand quite naturally.

So what happens when an instructor takes activities that students might naturally enjoy and make them just another assignment? I call this "schoolification," which is when a teacher deflates student interest in an activity or project by assigning points, a grade, or any other requirement that students might otherwise resist.

The first time I encountered schoolification, before I even had a name for it, was in a conference presentation where a professor described his use of Facebook in his classes. Each student in the class had to join his group on FB, they were required to comment on his posts, and they would "lose points" if they didn't do either of those things. My first thought was, wow, that's a great way to make students hate Facebook. Take something they like, make them use it in a way they don't want, then hold their grade over their head of they don't do it.

If the instructor is not careful, I think the same thing can happen with blogs, digital stories, flipped lessons, and cooperative learning (or any other activity for that matter). Students have to be held accountable for their professionalism, but how do we do this without schoolifying activities they might otherwise enjoy? This is a challenge I would like to learn more about.

How do you hold students accountable for their participation in class activities without schoolifying those activities that are intended to be engaging and fun.

Gradenomics

/ It's that time of year again, when I spend a lot of time reflecting on the semester and academic year. I have already posted once about this, and I have at least two more ideas incubating in my mind. The idea that came to me today as I graded final exams, calculated final averages, and entered final grades into "the system" is that universities - or perhaps my university - put a lot of emphasis on finals. This led me to consider whether or not there TOO much emphasis on final exams. As it is now, we set aside an entire week, shuffle the schedule, and give each professor 2.5 hours to administer the exam. Yet, I have not given a comprehensive final since my 2nd year of teaching higher education. Is this really worthy of its own week?

It's that time of year again, when I spend a lot of time reflecting on the semester and academic year. I have already posted once about this, and I have at least two more ideas incubating in my mind. The idea that came to me today as I graded final exams, calculated final averages, and entered final grades into "the system" is that universities - or perhaps my university - put a lot of emphasis on finals. This led me to consider whether or not there TOO much emphasis on final exams. As it is now, we set aside an entire week, shuffle the schedule, and give each professor 2.5 hours to administer the exam. Yet, I have not given a comprehensive final since my 2nd year of teaching higher education. Is this really worthy of its own week?

My first college teaching assignment was as a Master's student, and I taught public speaking. It was a massive faculty-directed, TA-taught course where they basically told us what to do. We had some freedom to teach any way we wanted, but we had to give the same assignments and grade using the same rubric. If our overall GPA was too high, we got a personal note from the course director telling us to grade harder. We also had to give a comprehensive final, which seemed totally ridiculous for a public speaking class.

Since those days, I have jockeyed between giving a final project (portfolio, paper, etc.) and giving the last test during the final time slot. My current university is adamant about professors doing something during finals week, so I have been using that time to give the last exam. I have also used this time to have students present their final projects, but it just seems contrived to me and seems to always fall a little flat. Some of the more adventurous faculty have the students bring food and they have a party.

My point is, there is a certain amount of hype associated with finals that I am starting to think is unnecessary. Whereas my students typically cram for the first two exams, they spend days and days studying for the last exam. And what is the payoff? Actually, the course average was lower than the second exam even though the exams were about at the same level of difficulty. I have exams weighted so that each test accounts for about 13% of the final grade. I did this a few semesters ago because I wanted the exams to mean something. Before I weighted the exam scores, a student could do poorly on exams and still eek out a decent grade by getting some of the "sit-and-get" grades, such as attendance or participation. Basically, taking the exam counted the same toward the course average as showing up to lecture and surfing Pinterest for an hour. So, what does this mean in terms of the last exam's impact on the overall grade? Here are some points to consider (remember, this is based on a scale where each exam contributes 13%, or 39% total, toward the overall grade):

- 35 out of 53 students got a score on the final within 2 percentage points of their current average. Mathematically, this had absolutely no impact on the final grade. For example, if a student was sitting at 91.21% and got a 93% on the final, the overall average was raised to 91.55% (I'm making these numbers up, of course, but they are pretty accurate to what I observed). Unless a student was a fraction of a percentage point from the next grade, this had no impact. It was just damage control.

- If a student scored 10 percentage points higher or lower on the final than the overall average, it meant a difference of 1 percentage point either way. In fact, this held true for every 10 percentage point differential. For example, getting a 75% on the test would lower the average from 85 to 84. That also means that getting a 100% on the test would only raise the average from a 85 to 87 (and that is a generous estimate). This is the difference between a B and B+, which is hardly the Hail Mary the students think it is.

- 9 out of 53 students went down one grade based on their final exam score, and each of them was 1 point or less from the borderline. That is, they went from a B+ to a B, but they started at 87.1% not 89.9%.

- Only one student went UP a grade based on the final exam score, and the starting average was already less than a percentage point from the cutoff.

Are you confused yet?

I am not advocating students completely blowing off a final because it won't make a difference in the long run. Students should always give their best effort no matter what. I also know that students spend just about as much time eating junk food and complaining about their professors during "dead days" as they do studying. I am just wondering if we should put so much emphasis on that one week when it's really the students' body of work throughout the semester that compiles their course average.

I am curious to know how others handle finals, and if they have more (or less) of an impact in your courses than what I have described? How are finals handled in other disciplines? Should they be more high-stakes, or are they just hype?

Dealing with Disappointment

/ I have been teaching for nearly 20 years, and I have seen just about everything. Throughout the many life changes I have experienced in that time, teaching, oddly enough, has been one of the constants in my life. Early in my career I would stay late at school and come home to an empty apartment. Soon enough, I was finding ways to have lunch with my wife over our short lunch breaks. Then I was rushing home after teaching so I could spend time with my babies. Now I have to be creative in order to balance my teaching with things like baseball, gymnastics, theater classes, church, committees, writing, and staying connected to family. During all this time, students have come and gone from my classes, hopefully taking something with them that will help in their life journey.

I have been teaching for nearly 20 years, and I have seen just about everything. Throughout the many life changes I have experienced in that time, teaching, oddly enough, has been one of the constants in my life. Early in my career I would stay late at school and come home to an empty apartment. Soon enough, I was finding ways to have lunch with my wife over our short lunch breaks. Then I was rushing home after teaching so I could spend time with my babies. Now I have to be creative in order to balance my teaching with things like baseball, gymnastics, theater classes, church, committees, writing, and staying connected to family. During all this time, students have come and gone from my classes, hopefully taking something with them that will help in their life journey.

Teaching requires a lot of creativity and problem solving because no matter what is happening in your life, you have to try to do your best for the students. In my career I have had to deal with crazy parents, over-scheduled meetings which force me to plan my lessons late into the night, hectic travel schedules for the sports I coached, sleepless nights, unexpected family crises, unpredictable weather, and disruptions to the school day. All in all, I would say I have done a pretty good job of paddling and finding the current. There is, however, one aspect of teaching with which I have not dealt very well.

Disappointment.

Maybe it's because I expect myself to be perfect. Or amazing. Or brilliant. Perhaps I spend too much time comparing myself to my peers and wanting to be the big fish in the pond. I already know I put too much stock in my course evaluations and Rate My Professor and any other metric I can find to evaluate my worth as a teacher, so maybe that feeds my disappointment. It could be that my expectations are too high, and while I perceive the response to a good class to be a standing ovation, my students are just anxious to meet their friends for lunch. No matter what the cause - and it's probably a complex mix of those factors I already listed, along with some I haven't identified - disappointment has always been a tough pill to swallow.

For the better part of this semester, I have been dealing with disappointment: in myself, in my students, in the fact that I didn't foresee some of the problems with one of the classes I have been teaching. Since the third week of the semester, things took a downward turn and despite my attempts to make the class better it has not been enough to make it a positive experience for anyone involved. Like I said, very disappointing.

It would be easy to wrap myself in self-pity, curl up in bed, close my eyes, and just wait for the semester to end. Trust me, I have considered that many times, and perhaps in small ways I have done some of that. However, as the self-reflective navel-gazer that I am, the ultimate question is this: What do I plan on doing about it? Other than venting to a few colleagues, which I have done more than I care to admit, I can't help but abstract some lessons from my disappointing semester.

Disappointment reminds me that I care.

If teaching and teaching future teachers about teaching was not a big deal to me, this would be easy to shrug off. Blame the students and move on. But this does matter to me and I understand the importance of what I am doing. No one is guaranteed that living out their passions or purpose or calling will be without setbacks. The setbacks actually remind us how closely our calling, purpose, and passion are woven in with our very being.

Disappointment reveals areas to get better.

Do you know which of my classes have historically gone the worst for me? Those which follow a class which has gone really well. If I think I have reached superstar status, where is the incentive to do things better, to be self-reflective, or try new ideas? There is no such thing as cruise control in teaching, and just because a certain approach or teaching style worked with one class does not mean it will work the next time. As long as I am teaching, there will be aspects of my practice that need to be revised, refined, or removed. It's hard to see those things when I am blinded by my own awesomeness.

Disappointment reinforces what is constant.

Even though I have to adapt every class based on the unique dynamics created by the students and circumstances, there are some elements of instructional practice that should never be compromised. High (yet reasonable) expectations. Timely feedback. Positive teacher to student relationships. Close monitoring of student engagement. Consistency. Fairness. Preparation. These make up the foundation of a healthy, vibrant class. I may be stuck with a class full of disengaged, apathetic, know-it-all students (speaking in general terms, of course ... not any particular class), but that should not change those core elements of effective teaching. If anything, the tougher the students, the more I should lean into those aspects of teaching that have been proven over time. Don't play off your students' responses because chances are they stayed up too late, woke up minutes before class, and put off their assignment until the last minute. As a baseline, my teaching must be one of the constants in their lives.

Honestly, I am thankful things did not go as well as I had hoped this semester (in one class at least ... the others went great). I have a lot to learn, a lot to improve, and a long way to go. Adversity causes everyone to either wilt or get stronger, and I choose the latter. The day I think otherwise about my teaching is probably a sign it's time to choose a new career. Thank you, disappointment, for the not-so-gentle reminder.

Outsmarting the LMS: Embedding Google Docs

/![]()

I generally love all things Web-related: social media, digital media, coding, learning management systems. You name it. But there are two things I absolutely hate and will avoid whenever possible. Uploading and logging in. I hate them both. They use up valuable time. They're obnoxious. So, I'm left with two options. I can either bite the bullet and just put up with both of those feudal tasks, or I can find a way around it.

Obviously, I chose the second option.

I have been doing this for a few years now, and it really has saved me a lot of time and frustration. This is why I would like to pass on the golden nugget known as embedding Google Docs in your LMS.

Step One: Convert to Google Docs

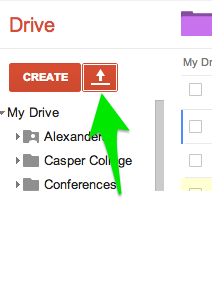

Before you can embed a Google Doc in your course shell, you have to have a Google Doc to embed. Most of the docs I use in my class (e.g., assignment descriptions, syllabi, tutorials and FAQs) originally existed as Word docs. Google makes it really easy to convert Word docs into Google Docs. You simply to go your Google Drive, click upload, and choose to convert the document (see below)

In the event you want to create a Google Doc from scratch, you can read this help document directly from Google. They've already done the work so I don't have to!

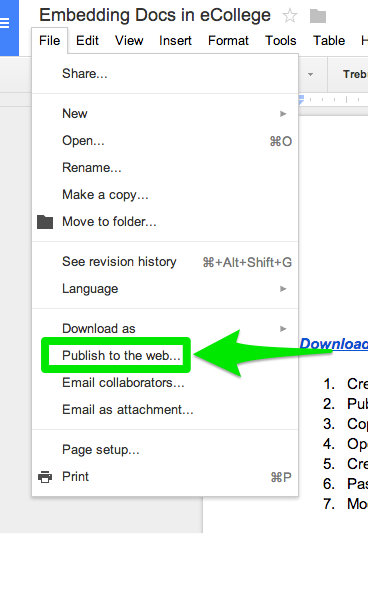

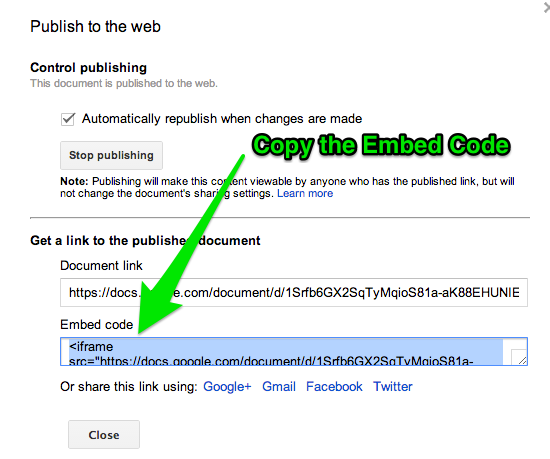

Step 2: Grab the Code

After you have created your Google Doc, you will need to grab the HTML code to add to eCollege. You can see this process in the images below:

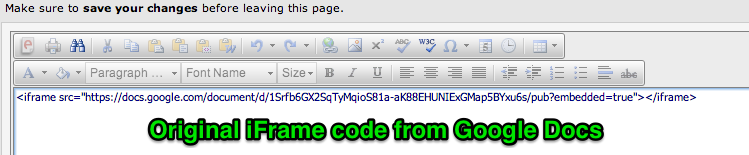

Step 3: Paste and Modify the Code

Now that you have the code in your clipboard, you need to go to the page in your LMS where you want to embed the Google Doc. The following screenshots are taken in eCollege, but there is probably a similar feature in all LMS products.

Notice the extra code I added to the original iFrame code in order to make sure the entire document displays in the LMS. If you do not add the width and height code, it will show up as a small box on the LMS page you created. The width should always be 100%, but the height may vary to ensure the whole document will fit in the frame without extra scrolling. The end result looks like this below:

The beauty of this technique is that when I make a change to the Google Doc, it immediately shows up in eCollege! No uploading and replacing old documents each semester. When I copy my course shell each semester, the HTML is still there so I only have to modify the original Google Doc. I don't think I will ever go back! So, give this a try and see how it works for you. You can also watch an archive of this Google Hangout where I showed this technique to some colleagues. Good luck!

TCU Lyceum 2013

/

Last week I had the opportunity to speak about educational technology to a group of 26 principals from around the state. When I say a "group of principals," what I really mean is "some of the very best principals" in the state. All of the superintendents in the state were contacted and asked to recommend their highest performing principals for the TCU Educational Leadership Lyceum 2013, and these principals were among those recommended and accepted. To say I was intimidated would be a huge understatement. I have taught classes to large groups of people virtually everyday for nearly 10 years, so it would stand to reason that I was up for this task. The truth is, I analyzed, planned, re-analyzed, over-planned, and perseverated over this presentation for weeks.

I will be the first to admit my presentation was kind of all over the place. I started with something about the past and future of educational technology ("Let's start by talking about the invention of fire ..."), then I mentioned something about the myths and actual findings of ed. tech. research, and I ended by showing them a few tools/activities that I like to use in my classes. Since this was my first presentation like this, I made the common rookie mistake of trying to do too much within such a short time frame. The presentation was scheduled for 3 hours, which seemed like a lot of time, but once I got the participants involved in some activities, it flew by. As usual, I left the presentation with a pretty good idea for what went well and what I would do differently if I were to get this opportunity again.

Here are my main lessons from this experience:

- Less is more. People can only remember a certain amount of information, and they are probably more likely to remember a handful of compelling activities than a bunch of information.

- There are no style points. Actually there could be, but if they distract from the One of the main mistakes I made was trying to switch between too many programs. I was projecting my main points using the Broadcast feature in SlideShark. I was mirroring the display of my iPad using AirServer when I wanted to demonstrate something. I was pulling information from several different browser tabs. It got confusing for me, which means it was definitely overload for the participants.

- Use activities to illustrate a point rather than making them the point. I knew this as I planned the presentation, and I still gravitated to this error like a moth to a porch light. I usually like to arrange a presentation around 3-4 big ideas, and I have activities that make them come to life. This time, I did that for 2 out of 4 of my main points, so it should come as no surprise that only half of my main points went over well. Anyone who has done this sort of thing for awhile knows you can't just show people tools. One fourth of the audience is two steps ahead and bored, one fourth is with you, and half of them are totally lost. I had to re-learn this lesson the hard way.

Overall, I feel very fortunate to have been included on the program for this amazing group of principals. Their energy and love for students was evident in just the brief time I was with them. They asked great questions and willingly participated in the activities I had set up for them. Many of them followed along and took notes on their personal devices, which I believe increases the probability some of these ideas will live on beyond the short workshop. I am also thankful for my colleagues at TCU who invited me to be part of their team. I look forward to many more excellent experiences in the future.

It's not you, it's me

/For several years, I have asked students to fill out a Student Information Survey at the beginning of the semester. I adapted the same survey from semester to semester, but it essentially consisted of the same questions. Sometimes it was worth a grade, other times not. Sometimes I made the fields required, sometimes not. Since I have typically taught tech-integration courses for the past several years, most of my questions were technical in nature. I wanted to know such things as their current tech setup (type of computer/OS, access to other devices, etc.), experience with current tech trends (social, mobile, Cloud, gaming, etc.), the intensity of their love/hate relationship with tech, and how their teachers in the past have used it. I also asked a a couple of questions about how they learned best and about any teaching experience they had. Overall, this Student Information Survey was not very exciting, but it helped me establish a baseline for what I was dealing with. Now that I do not teach tech integration classes anymore, I have found my current survey needs to be updated as well. For one thing, I have started calling it a "questionnaire," which may just be a semantic issue, but it seems to capture what I am actually doing. The most notable change, however, is the questions themselves. Instead of getting descriptive data, I want the students to be introspective about themselves as learners. Based on a few studies I have read lately, I have learned that student evaluations of their professors are based more on their self-concepts as learners than on the efficacy and characteristics of the professor. For example, one study I looked at used a hierarchical regression analysis to investigate the relationship between students' academic self-efficacy and professor characteristics. The result of this study showed that students with high academic self-efficacy tended to give high ratings to professors with characteristics such as content expertise, professionalism, and disagreeableness (i.e., argues, challenges, steps on toes). On the other hand, students with low academic self-efficacy tended to give high ratings to such professor characteristics as compassion, helpfulness, and student-centeredness (though I personally find that trait to be problematic). The Social Exchange Theory is alive and well in the classroom.

In essence, the college classroom is no different than life in general: People evaluate others based on how they feel about themselves.

In response to this belief about my students, I want them to think a little more deeply about themselves as learners and unpack some of the jargon they tend to throw around. One example of psycho-babble jargon students tend to use is "engaged." For example, when I ask the question, "When do you learn best?" they will often respond by saying, "When I am engaged in my learning." My first response is, "Well, yeah, that's kind of how learning works. It's not a passive process." But I have really started to think more deeply about what students mean by "engaged." I always assumed engagement was a trait of the learner, as in, I am listening, taking notes, asking questions, participating in the discussion: I am in engaged. Based on my experience in one class last semester, however, I suspect many students have a completely different vision for what "engaged" means. I now believe they see this as a trait of the instructor, as in, you are doing things in class that I deem worthy of my attention. The professor is engaging the students. It all comes down to locus of control. In a perfect world, both of these conceptualizations of "engaged" are true, and the professor is carefully thinking about how to present ideas in an organized and compelling way, while using strategies to draw the students into the process. At the same time, the students buy into this and are internally motivated to participate. Both parties fully understand their role in the process and take it seriously. Of course, I have no idea if any of this actually true, or if I just obsessed about it way too much and displaced a lot of my own insecurities onto the students.

This is why I am asking new questions. I want to know how my students evaluate themselves as learners, how they describe "engaged learning," and how they know if they have learned something or not. I am also including a question that asks them to rate themselves at multi-tasking. This item alone will probably explain 90% of the variance in test scores. In case you have never read my reflections on teaching college students, I believe multi-tasking is a horse apple dipped in a cow pie and sprinkled with bird droppings.

My purpose in asking these questions is two-fold. First, I want my students to honestly think about themselves as learners. I am not expecting light bulbs or fireworks, but I do want to push this issue to the forefront. Second, I want to know their (mis)conceptions about learning and teaching so I can address it. Once I know what they think about these important concepts, I can show them research that either confirms or refutes their beliefs. More importantly, it gives me the opportunity to make the class not just informational, but also transformational. Any time a person has the chance to reflect and say, "I used to think ..., but now I know ..." it opens the door to personal growth. Isn't that what all teachers hope to engender in their classrooms?

So, what strategies or activities do you use to learn about your students? How do you use that information? Is it valuable? Take a minute to let me know what you think.